It all started with my grandfather. He had taken over

pastoral duties at the church which was part of a local retirement community.

One Sunday evening, he introduced me to a member of his congregation – a WWII

veteran who had flown night fighters for the Army Air Force.

It would be a gross understatement to say that I was

awestruck. Even as a kind of obnoxious young teenager, meeting an actual WWII

fighter pilot was a huge honor for me. I wish I could remember what I asked

him, but I guess I made a reasonably good impression, because for the next

couple of years my grandfather played middleman, conveying a few neat aviation

pictures and books from Mr. Stewart to me.

The pictures depicted aircraft from WWII, but not the

familiar Mustangs, Spitfires, Corsairs, Hellcats, and Lightnings. Not even the

dreaded enemy BF-109s, FW-190s, or Zeros were seen. Instead these aircraft were

the bulky Tigershark, sleek Mosquito, oddly proportioned Beaufighter, and the

sinister Black Widow.

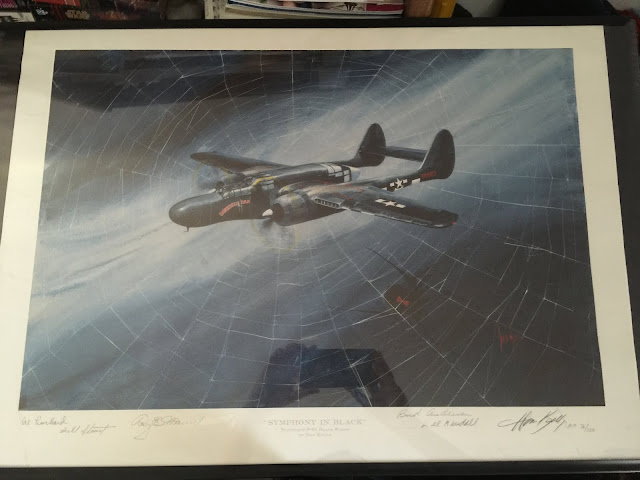

|

| My personal copy of Symphony In Black, SN #79/100. Signed by the artist, Dan Kelly, and Bill Stewart, Al Lockard, Ray Mann, Alvin E. "Bud" Anderson, and Lee Kendall |

|

| Three of the four aircraft in Gary Olson's Night Fighters series. From Left to Right is the DeHavilland Mosquito, Bristol Beaufighter, and Northrup P-61B. Not shown is the Douglas P-70. |

I was hooked. I knew very little about night fighters, a

side of the WWII air war that is rarely written about, but was no less

important. More than that, staring at these pictures made me want to see one of

these aircraft in person – the P-61 Black Widow, the same aircraft that Bill

Stewart flew.

Now in the 1990s, if you wanted to see an intact P-61, there

were exactly two places in the world you could go: the National Museum of the

United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio,

USA; or the Beijing Air

and Space Museum in Beijing, China. For me, both those destinations were

equally unobtainable. Oh, the National Air and Space Museum had a Black Widow

as well, but it was tucked away in one of their storage facilities, another

artifact they had no room to display.

Those

pictures travelled with me. I grew up, got married, and Symphony in Black went

up in our first apartment. We bought our first condo, and Symphony in Black went

up office (and eventual nursery) while the India Ink drawings split their locations

between the living room and office.

Time passed, and with the opening of the Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles, the ranks of intact, viewable P-61s grew to three. Still, as a

resident of the West Coast, Washington D.C. wasn’t any more convenient than

Dayton or Beijing. And that’s how it remained, until an interview brought me

out to Washington D.C. in July of last year, with enough time in my schedule

after arrival to spend a few hours at the Udvar-Hazy Center.

Seeing the aircraft I’d dreamed about for so many years in

person was, to be honest, a bit overwhelming. Sitting in the museum, surrounded

by other aircraft of the era, gave a real scale of just how big the P-61 was

compared to its contemporaries.

|

| Longer shot to show the scale of the P-61. It dwarfs the single-engine fighters of the same era displayed near it, and really is only outshone by the B-29 Enola Gaybehind it. |

I saw a lot of amazing, one of a kind aircraft that day. But

when closing time came, the P-61 was the one I came back to for one last look.

I’d also like to note that the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum has a

fourth P-61, which they’ve been slowly restoring to flight status since 1991. Assuming

they eventually get it completed, I fully intend to be there, to see and hear

one of these amazing aircraft fly again!

No comments:

Post a Comment